The 1924 Chamonix Olympics: where winter sports history began

Discover the fascinating story of the first Winter Olympic Games held in Chamonix and how it shaped modern winter sports as we know them today.

1924: Chamonix's Historic Moment

One hundred years ago, between January 25 and February 5, 1924, the small Alpine town of Chamonix-Mont-Blanc made history. At the foot of Europe's highest peak, the valley hosted what was then known simply as the International Winter Sports Week. Nobody could have guessed that this modest gathering would become the first-ever Winter Olympic Games.

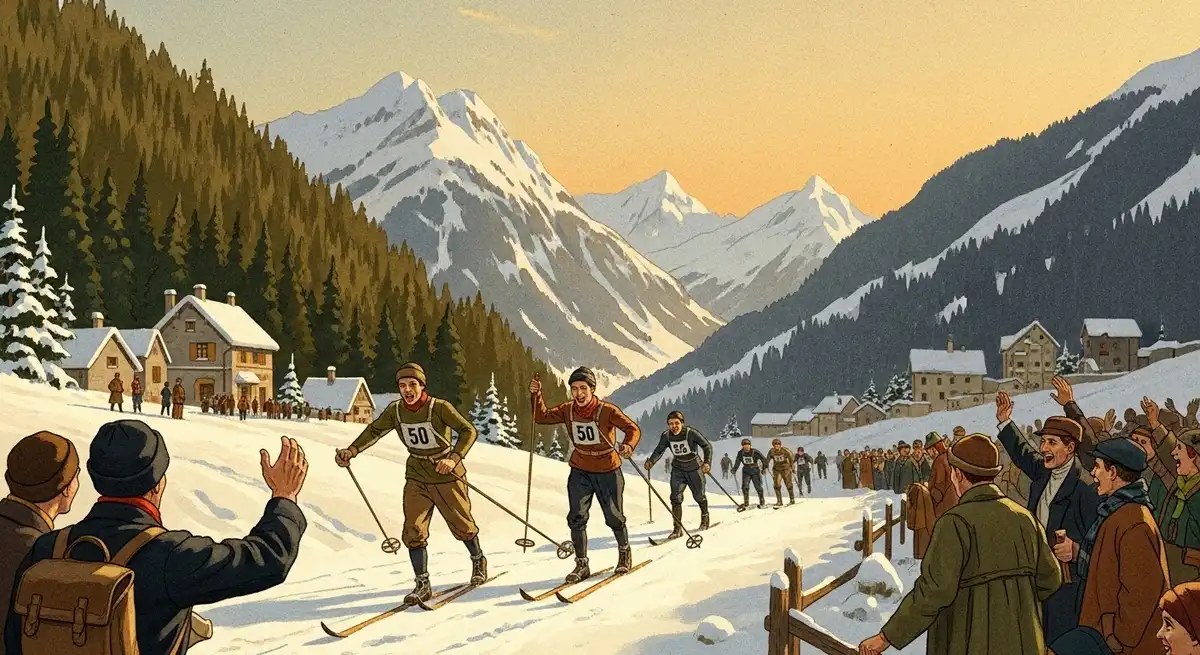

The scene was something out of a mountain dream. Steam rose from the trains at Chamonix's tiny station as athletes arrived wrapped in wool and leather. Locals lined the streets, waving flags from seventeen nations. The snow creaked underfoot, the cold bit through thick coats, and excitement buzzed through the frozen air. It was the beginning of a new chapter in sporting history.

The Vision Behind the Games

The idea of winter Olympics was not born easily. Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic movement, was initially against separating winter and summer games. He feared the new event would overshadow the Olympics he had worked so hard to revive.

But the popularity of winter sports was exploding across Europe, especially in the Nordic countries, where skiing was not just a sport but a way of life. Norway, Sweden, and Finland led the push, and France, eager to showcase its Alpine heritage, proposed Chamonix as the perfect setting. The valley already had good snow, basic infrastructure, and a growing reputation among adventurous travelers.

In January 1924, the experiment began.

The Pioneering Sports

Nordic Events

The heart of the program came from the North. Cross-country skiing, ski jumping, and the Nordic combined dominated the schedule. The fifty-kilometer cross-country race became a legend in itself. Thorleif Haug of Norway, battling snow, wind, and exhaustion, crossed the line after nearly five hours and became the first Winter Olympic champion in history.

Norway's technical skill and stamina set a standard that defined the Games. By the end of the week, the Norwegians had claimed seventeen medals, four of them gold, and cemented their status as the masters of snow.

Figure Skating Excellence

Figure skating added elegance to the mix. Performed outdoors under the soft winter light, the routines were as much a test of endurance as artistry. Austria's Herma Szabo captivated the crowd with her grace and precision, winning the ladies' event, while Sweden's Gillis Grafström defended his Olympic title from 1920 (when figure skating was still part of the Summer Games). The pairs competition brought gasps and applause, marking the moment when skating truly became a performance art.

Ice Hockey Drama

Then came the noise and the Canadians. Represented by the Toronto Granites, Canada's ice hockey team dominated the rink with relentless energy. They scored 110 goals and conceded only three across five games, ending with a crushing 6–1 victory against the United States. Their play was fast, precise, and unlike anything Europe had seen. It was the birth of Canada's Olympic hockey dynasty.

Many visitors today are surprised to learn that alpine skiing, the downhill racing we know today, was not yet part of the 1924 Olympic program. At that time, skiing was still viewed as a Nordic pursuit focused on endurance, rhythm, and technique rather than speed. The idea of rushing down a mountain on wooden skis was considered daring and even a little reckless.

It would take another twelve years for alpine skiing to enter the Olympic stage, making its debut at the 1936 Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Germany. But in Chamonix, the spirit of the sport was already alive. A few brave locals and visiting mountaineers were experimenting with descents on the slopes of Brévent and Les Houches, unknowingly preparing the ground for what would soon become the defining sport of the Alps.

Chamonix's Olympic Legacy

The Games were not perfect. The timing equipment froze, the weather shifted hourly, and journalists wrote with numb fingers. But when it was over, the world agreed: winter sports had earned their place on the Olympic stage.

Two years later, in 1926, the International Olympic Committee officially recognized the Chamonix event as the First Winter Olympic Games. The experiment had become a tradition.

For Chamonix, the impact was immediate and lasting. The infrastructure built for the Games transformed the valley. Roads were widened, trains ran more frequently, and new hotels and cafés appeared where there had once been farmland. The event turned the quiet Alpine town into a symbol of winter adventure.

The old ice rink evolved into the Stade Olympique, still used for competitions today. Skiers, snowboarders, and mountaineers now follow in the tracks of those early pioneers. The same mountains that challenged the 1924 athletes, Brévent, Grands Montets, and the Aiguille du Midi, continue to inspire new generations of adventurers.

A Lasting Spirit

The 1924 Chamonix Olympics were more than a competition. They were an act of imagination, proof that winter could be a season of glory, not just survival.

A century later, when skiers carve down Mont-Blanc's slopes, they unknowingly echo those first brave Olympians. The cold, the light, the sound of snow under skis, all of it connects back to that January morning in 1924, when the world discovered that winter could be beautiful, daring, and Olympic.