The first tourists in Chamonix

Long before cable cars, crowds, and après-ski bars, Chamonix was discovered by a handful of curious English travelers armed with notebooks, walking sticks, and too many layers of wool. At the end of the eighteenth century, the valley was little more than a cluster of stone houses surrounded by glaciers and forests. The few outsiders who ventured there were scientists and explorers drawn by the mystery of Mont Blanc. Horace-Bénédict de Saussure's 1787 expedition marked a turning point: the valley, until then remote, began to enter the imagination of Europe.

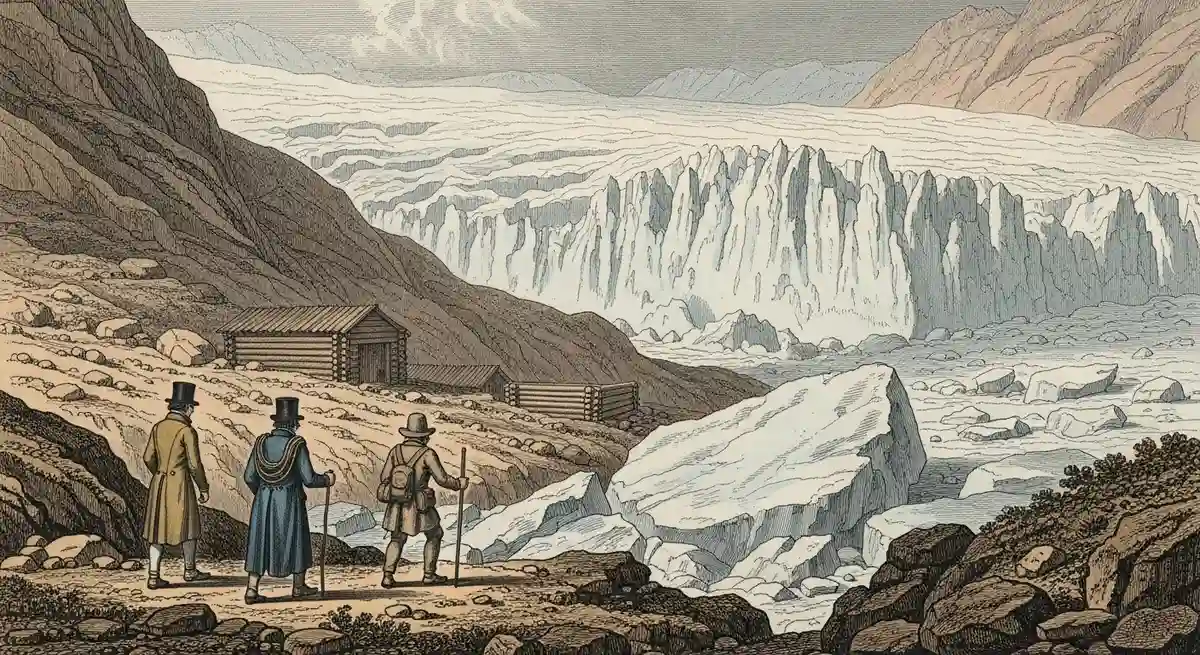

By the early nineteenth century, that fascination had crossed the Channel. Travelers from London, often aristocrats, writers, or artists, began arriving in Chamonix in search of sublime landscapes and adventure. They came not for skiing but for scenery, wandering the paths to the glaciers in long coats and polished boots, sketching, journaling, and proclaiming their delight in the language of the Romantic age.

The Birth of Alpine Hospitality

As their numbers grew, so did the hospitality. Madame Coutterand was among the first to open her home to visitors around 1770. The Paccard and Simond families soon followed, turning simple dwellings into welcoming inns. In 1816, the Charlet brothers built the Grand Hôtel de l'Union, offering warm baths, fine wines, and an air of refinement that astonished travelers used to rough alpine shelters. Only a few years later, Jean-Pierre Tairraz established the Hôtel de Londres, clearly aimed at the growing English clientele. Its name alone promised familiarity, but it also served tea, carried London newspapers, and made its guests feel at home beneath the shadow of Mont Blanc.

Albert Smith and the Victorian Fascination

Among those who helped turn Chamonix into a legend was the English writer and humorist Albert Smith, whose lectures in London brought the Alps to Victorian audiences. He spoke of the difficulties of climbing, the eccentricity of the guides, and the sheer spectacle of the mountains with self-deprecating wit. Describing one of his glacier crossings, he wrote, "How on earth they contrive to traverse it, I cannot very well make out," capturing the mix of awe and absurdity that defined those early alpine adventures.

A Fashionable Stop on the Grand Tour

By the 1820s, Chamonix had become a fashionable stop on the Grand Tour. English travelers wrote about the Alps as if they were moral lessons carved in stone, and their stories inspired more visitors to follow. One account recalls gentlemen sending empty wine bottles sliding down the Mer de Glace for sport, watching them bounce and vanish into the crevasses with great amusement.

Two centuries later, the charm remains: a cup of tea, a view of Mont Blanc, and that same quiet sense of wonder the English brought with them. The valley still holds the same strange magic, wild yet civilized, remote yet welcoming, and perhaps that is exactly why Chamonix has never gone out of style.